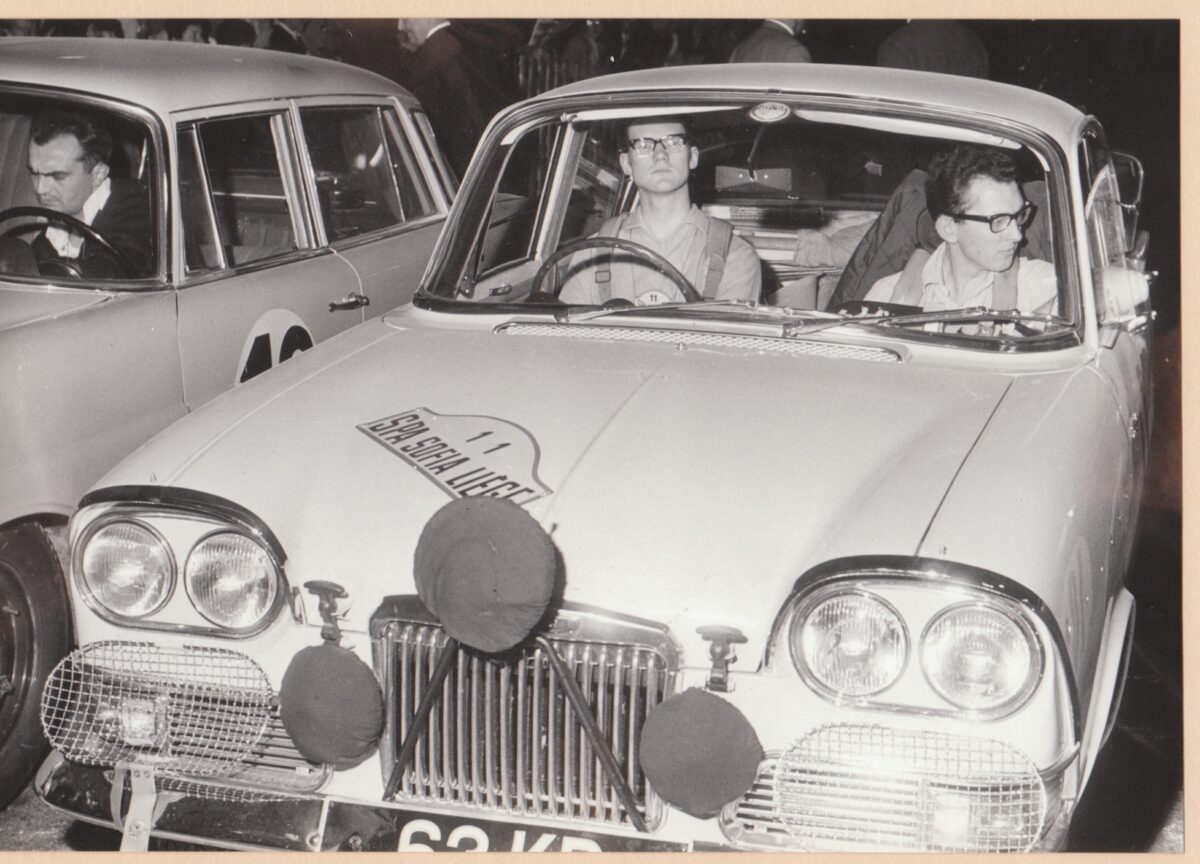

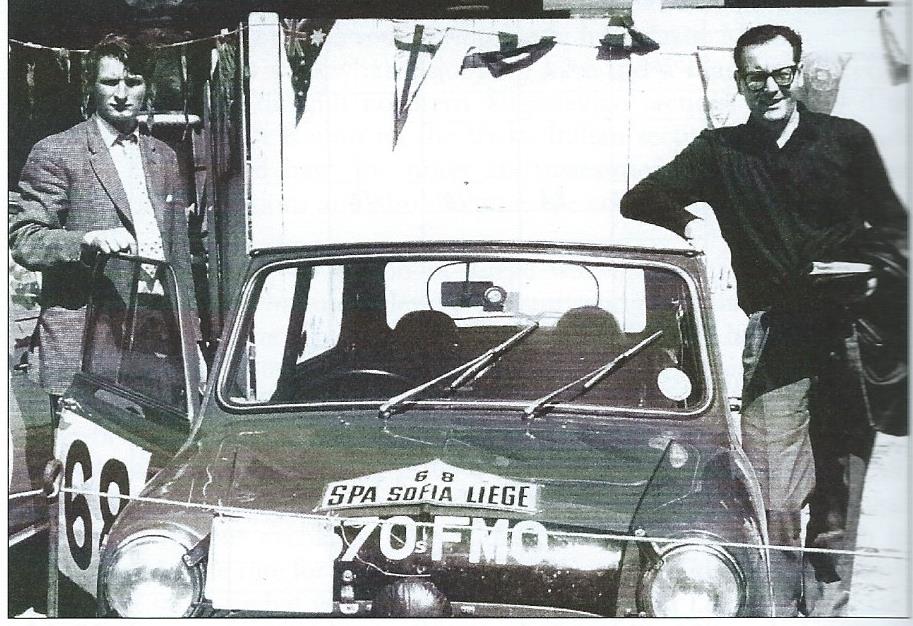

All of our ‘regular’ readers will be well aware of Mike Wood and John Wadsworth’s exploits on the 1964 Liege. I posted this story on a Facebook page and recieved a reply of another contestants, Doctor Beatty Crawford, reccollections of this car breaking event.

Our 1964 Spa-Sofia-Liege rally.

The Royal Motor Union Club wanted only one car to finish the Spa-Sofia-Liege rally. In 1964 they almost achieved their objective. Of ninety-seven starters just twenty-one made it to the finish and then only because the organisers extended the maximum lateness by two hours. Today it is difficult to believe just how hard this rally was, a virtually non-stop drive across the worst roads in Europe, from Belgium all the way through Yugoslavia to Bulgaria and back. Average speeds took no consideration of stops for fuel or food. There was virtually no servicing. From the start in Spa the rally went through Austria and into Italy, where the event began in earnest. After reaching Sofia in Bulgaria the rally simply turned around after one hour rest and began the long trek home with the timed runs over the gravel-covered, fearsome Vivione, Gavia and Stelvio Passes. This is from the obituary on the winning co-driver Tony Ambrose: “The 1964 Spa-Sofia-Liege was by general consensus the toughest road rally ever held in Europe, an event of a format that could never be held these days. Rauno Aaltonen still praises Ambrose’s part in their momentous victory in an Austin Healey 3000. Crews faced four days and nights with no scheduled chance to sleep: Tony planned it all, he forced me to sleep even at moments when I wasn’t so tired. He even drove one 77-mile section at night in 52 minutes. We were going at maximum speed, 150 mph, on cobbled roads amid unlit horses and carts, yet he was such a safe driver I slept through it all! He could have been just as good a driver as he was a co-driver.”

Adrian Boyd and I took part in a Humber Sceptre. We were sponsored by Alan Fraser Racing. Alan was a very wealthy, slightly eccentric, Rootes dealer in Hildenborough, Kent and took a liking to Adrian after he had won the Circuit of Ireland in 1958. He basically ran Rootes works prepared cars as a private entrant. We drove for him on the 1964 RAC rally in a Humber Sceptre and finished 21st overall. On the Circuit of Ireland we were given a Sunbeam Tiger but severely blunted its teeth when we aquaplaned off the road into a large rock on Sally’s Gap. Alan had entered two other cars, Bill Bengry and Ian Hall in a Sunbeam Rapier and John La Trobe and David Skeffington in a Humber Super Snipe.

We were like babes in the wood when it came to the Marathon. No recce or Tulips so all the route was on maps and I can tell you that the map in Yugoslavia was no better than a quarter inch to the mile. One of my jobs was to obtain cash for petrol and emergencies. I had envelopes for Belgium, Germany, Austria, Italy, Yugoslavia and Bulgaria since there were no credit cards in those days. Our only asset, so we thought, was young age and a slow but reliable car.

The first part of the route was easy. We departed Spa in southern Belgium, home of the F1 track and straight on to the German autobahns. Then off the autobahn onto A roads to Bregenz on the Austrian border. But we never even made it to Bregenz. At about 4.00 am a noise suddenly developed in the gearbox. A few miles later we were dead in the water. The gearbox drain plug had vibrated loose and fallen out. Loctite had been invented yet. Apparently the plug hadn’t been wired to prevent it loosening.

All we could do was sleep and wait until daylight. We were awaked at about 6.00am by German Polizei who had found us parked at the side of the main road. “Oh, oh” we thought we are in trouble, but no, in sign language and broken German we explained that we were “kaput.” The very friendly cops soon produced a rope and towed us to a garage in a village called Wangen. It was still only 7.00am and we waited another hour until the garage owner arrived. His name was Herbert Schek. He spoke English and we told him our story. He asked us where we were from and we said Northern Ireland. “Northern Ireland” he said, “Do you know Sammy Miller?” It turned out that he too was a top trials rider and was a great admirer and friend of Sammy.

From then on we were royally looked after. He took us to his house where we stayed. Herbert and his wife Annaline fed and watered us and he gave us the use of a hoist in his garage where we removed the broken gearbox. It was hard work since the two us had very little knowledge of anything mechanical. Meanwhile Adrian had phoned the bad news to Alan who arranged for a new gearbox to be shipped down by train from somewhere in Germany. It arrived next day and we soon had it installed and on our way again. We decided to meet up with the rally on its way back at a time control at the bottom of the Stelvio Pass.

We had no idea who would be still in the rally but both Bill and John arrived. Bill was from Leominster in Wales and many times “Motoring News Rally Champion” and very much a VW exponent. A bit like Robert McBurney, he was very good driver and an equally good mechanic. One of the major problems on the Marathon was punctures from nails on the roads in Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. Bill would sit in the back seat while Ian drove and took off the tyre and repaired the puncture while on the move! We tried to help us much as we could in our limited way and I had bought green grapes for the crews. I put a large bunch on the driver’s seat but Bill in his hurry to get going again forgot and jumped in on top of the grapes. I’m sure by the time he got to the top of the Stelvio, the wine was good, if a bit warm.

We followed them to Liege in case they would get into trouble, back through the border at Bregenz. Who was waiting for us with all sorts of food and drinks but Franz and his wife Annalie. Talk about hospitality. Bill and John made it to the finish without any problem and so Alan Fraser had two cars finish out of the 21. A remarkable feat.

I sometimes regret not being able to complete the entire event but the rally was never held again. It had become too dangerous and too anti-social. On the other hand, if ever there was a rally where “It’s like beating your head against a wall, it’s great when you stop” applies, this was it.

This is from an article in Retrospeed.

Exactly forty-five years ago a big red Healey 3000 driven by Rauno Aaltonen and navigated by Englishman, Tony Ambrose won the infamous Liege-Sofia-Liege Rally outright. In fourth place and winner of the Coupe des Dames, driving the diminutive SAAB, was Pat Moss, already a household name, not just for being Stirling’s sister but for also winning the Liege in 1960. Husband-to-be, Eric Carlsson, also driving a SAAB made it into second place behind Rauno.

Today it is difficult to believe just how hard this rally was, a virtually non-stop drive across the worst roads in Europe, from Belgium all the way through Yugoslavia and back. Average speeds took no consideration of stops for fuel, food or routine maintenance. Service crews were anyway pretty useless as the route never passed the same place twice. From the start near Spa the rally led down through Austria into Italy where the event began in earnest. Thirty miles south of Bled, Bo Ljungfeldt rolled his works Mustang and leader Henry Taylor disappeared over the edge and fell one hundred feet into a ravine, luckily without injury. Georges Harris hit a truck in his Lancia Flaminia and was reported as dead but this later proved more than a mild exaggeration. Other well known exponents suffered setbacks including Sydney Allard, Timo Makinen and Roger Clark. All soldiered on albeit running quickly out of time. It really is difficult to describe the conditions, cars were expected to keep going for hours on end over unmade stone-covered roads. All three works Triumph 2000s expired within twenty miles of each other while the inevitable punctures delayed both Roy Fidler and Paddy Hopkirk. Vic Elford retired his Cortina after running head on into a wall near Kotor. After reaching Sofia in Bulgaria the rally simply turned around and began the long trek home with the timed descents of the gravel-covered passes of Vivione, Gavia and, naturally, the Stelvio designed to catch out the tired crews. Stories of hardship abound. Carlsson lost one of his two cylinders after the Gavia, driving the final fourteen hours on 425cc while for the first time ever a Mini, the 1293 Cooper S of John Wadsworth/Mike Wood not only lasted the distance, but finished in 20th position. Citroen, the only manufacturer to have a team finish intact, won the coveted Team Award.

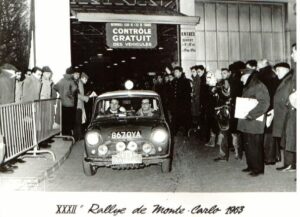

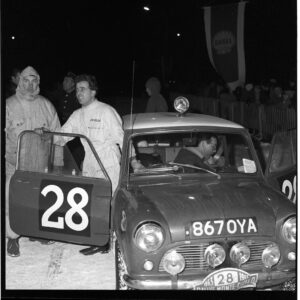

ould be Paris and Geoff let me know that the Paris starters had been allocated the early numbers, our own competition number was 28. I remember making a joke at the time, saying that with a little bit of luck, we could be the first car into Monte Carlo. Little did I know how true that joke would turn out to be?

ould be Paris and Geoff let me know that the Paris starters had been allocated the early numbers, our own competition number was 28. I remember making a joke at the time, saying that with a little bit of luck, we could be the first car into Monte Carlo. Little did I know how true that joke would turn out to be? remember this as we had a control at The Hague. I also remember that on the way to the Hague control I was doing my stint of driving on a stretch of Dutch autobahn. There was plenty of snow on the road and for some reason I must have lifted my foot off the pedal quickly and, for no reason at all, the car spun completely around crossing the centre strip. There was no barrier in those days, and I finished up on the opposite carriageway. Geoff had been sleeping and of course woke up with all the commotion going on. When I told him what had happened and that we were now going in the opposite direction, he simply said that I had better get it back through the gap I had caused and get on my way. With that comment he duly went back to sleep. I think the only damage sustained was a bent number plate, which remained bent throughout the event.

remember this as we had a control at The Hague. I also remember that on the way to the Hague control I was doing my stint of driving on a stretch of Dutch autobahn. There was plenty of snow on the road and for some reason I must have lifted my foot off the pedal quickly and, for no reason at all, the car spun completely around crossing the centre strip. There was no barrier in those days, and I finished up on the opposite carriageway. Geoff had been sleeping and of course woke up with all the commotion going on. When I told him what had happened and that we were now going in the opposite direction, he simply said that I had better get it back through the gap I had caused and get on my way. With that comment he duly went back to sleep. I think the only damage sustained was a bent number plate, which remained bent throughout the event. ed our way through France towards Chambery. Now came the important part of the event, over 9 hours of hard driving from Chambery to Monte Carlo over the southern French Alps, via many special stages and difficult road sections. With light snow falling in Chambery, and in the darkness of late afternoon, we left the time control 28 minutes after competitor No.1. We headed for the mountains and the first special stage which started about 7 kms. out of Chambery.

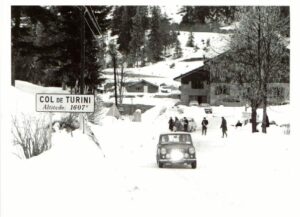

ed our way through France towards Chambery. Now came the important part of the event, over 9 hours of hard driving from Chambery to Monte Carlo over the southern French Alps, via many special stages and difficult road sections. With light snow falling in Chambery, and in the darkness of late afternoon, we left the time control 28 minutes after competitor No.1. We headed for the mountains and the first special stage which started about 7 kms. out of Chambery. We were using the marvellous BMC route notes which had been excellently prepared and checked by one of the full-time rally crews, without these notes life would have been difficult. The Chamrousse test was about 39 kms, again going quite high with the snow continuing to fall. Geoff was again at his best and we got to the end going quite well with no excursions off the road.

We were using the marvellous BMC route notes which had been excellently prepared and checked by one of the full-time rally crews, without these notes life would have been difficult. The Chamrousse test was about 39 kms, again going quite high with the snow continuing to fall. Geoff was again at his best and we got to the end going quite well with no excursions off the road. d special Dunlop studded tyres for the stage. This was the advent of studded tyres and these Dunlop ones were crude at that time. I think from memory that they did not have more than about 40 studs per tyre and even these were screwed in from the inside of the tyre. We gladly accepted the tyres, but I cannot honestly say that they made any difference to our stage times, in any case by now we could smell the Mediterranean and were more concerned in getting through the last few kilometres in one piece.

d special Dunlop studded tyres for the stage. This was the advent of studded tyres and these Dunlop ones were crude at that time. I think from memory that they did not have more than about 40 studs per tyre and even these were screwed in from the inside of the tyre. We gladly accepted the tyres, but I cannot honestly say that they made any difference to our stage times, in any case by now we could smell the Mediterranean and were more concerned in getting through the last few kilometres in one piece. junction out of La Turbie on the road down to Monaco we were immediately confronted by two gendarmes on their BMW motorcycles who started to flag us down. We wondered what we had done wrong, but without stopping us they gesticulated that we should follow them. There then started one of the fastest parts of the rally and we realised that, because we were the first rally car on the road, we were getting a typical French high-speed escort to the final control.

junction out of La Turbie on the road down to Monaco we were immediately confronted by two gendarmes on their BMW motorcycles who started to flag us down. We wondered what we had done wrong, but without stopping us they gesticulated that we should follow them. There then started one of the fastest parts of the rally and we realised that, because we were the first rally car on the road, we were getting a typical French high-speed escort to the final control. new that the rest would soon be following. We did allow ourselves the thought however, that there might have been a large avalanche behind us and that we might be the only finishers. We would have won everything then, including the Coup des Dames!

new that the rest would soon be following. We did allow ourselves the thought however, that there might have been a large avalanche behind us and that we might be the only finishers. We would have won everything then, including the Coup des Dames! aps. It was quite an enjoyable test for the co-drivers as we did not have to accompany our drivers. It was very relaxing for us all to sit enjoying a beer or two, watching our drivers perform on their own for a change. The outcome of the races did not alter the leading places, however. Eric Carlsson and Gunnar Palm in the SAAB won the rally. Pauli Toivonen in the Citroen was second and Rauno Aaltonen and Tony Ambrose in the Mini Cooper were third. Paddy Hopkirk in a works Mini Cooper was 6th overall.

aps. It was quite an enjoyable test for the co-drivers as we did not have to accompany our drivers. It was very relaxing for us all to sit enjoying a beer or two, watching our drivers perform on their own for a change. The outcome of the races did not alter the leading places, however. Eric Carlsson and Gunnar Palm in the SAAB won the rally. Pauli Toivonen in the Citroen was second and Rauno Aaltonen and Tony Ambrose in the Mini Cooper were third. Paddy Hopkirk in a works Mini Cooper was 6th overall.

at tells a story, a book which is of particular interest to members of the Lancashire Automobile Club and how their events amongst others help to shape the history of British motorsport before the Great War.

at tells a story, a book which is of particular interest to members of the Lancashire Automobile Club and how their events amongst others help to shape the history of British motorsport before the Great War. f dynamic balancing for engine parts, along with the origins and reasons for failure of Edwardian front wheel brakes on production cars. (picture right is Rivington Pike in 1912)

f dynamic balancing for engine parts, along with the origins and reasons for failure of Edwardian front wheel brakes on production cars. (picture right is Rivington Pike in 1912)